For dad.

There’s a story about my dad that, with each retelling, has become something of a family legend. It goes a little like this:

When I was scarcely a few months old, my dad’s company received an invite to exhibit at a technology expo in Japan. Back in the mid-80s the cold war made flight-paths challenging and the direct west-east journey that has since become the standard (at least, until 2022) was impossible. Instead, passengers would endure a near 20-hour journey from the UK to Alaska, before flying backwards across the international-date-line to Tokyo. Dad was reluctant to travel so far away so soon after my birth, but exhibiting in Japan was a huge opportunity for his company. Despite his reservations, he decided to go.

It was when the plane stopped to refuel in Anchorage that dad noticed something was off. He couldn’t shake a dull, nagging feeling in his gut. At first he thought it was nerves, or perhaps it was discomfort from the bumpy flight. Nothing to worry about. He’d be home before he knew it.

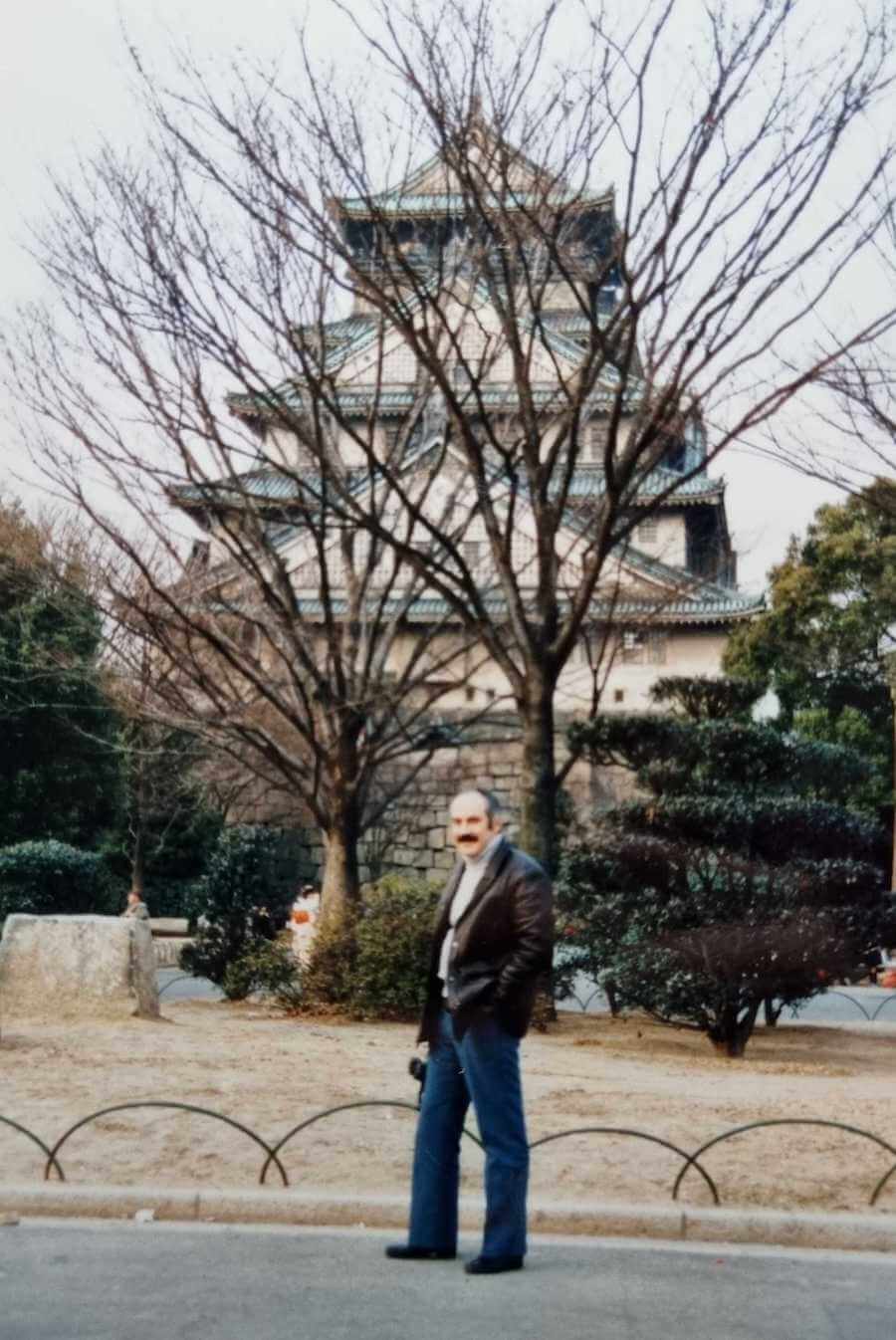

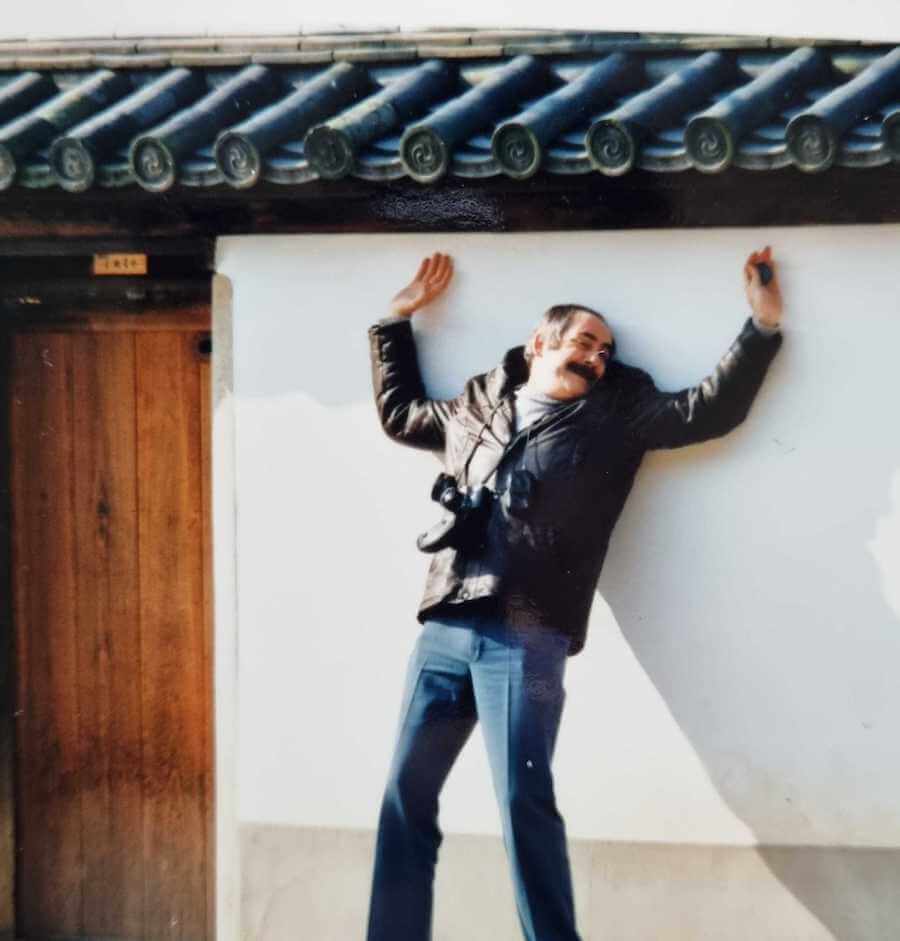

Upon landing, dad received the guided treatment that was customary for business travellers to peak-bubble-economy Japan. Bleary-eyed, he was rushed out on a no-expenses-spared trip seeing the sights of the Kantō and Kansai regions. He saw the neon lights of Tokyo before taking a bullet-train to the lively bars and restaurants of Osaka. He saw the temples of Kyoto and was mobbed by the deer at Nara. Amongst all the heavy drinking, food, sight-seeing and omotenashi, the expo was a huge success. Exhausted after two eventful weeks of networking, dad was ready to fly home.

As he was packing for his flight, the odd sensation came back. This time though, it was much more intense. Wincing at the now-very-sharp pain in his abdomen, he decided (as he often did) to try and walk it off. He grabbed his coat and set out from his hotel room. The pain only grew worse.

By the time he reached the lobby, he was having to steady himself against the wall to keep from falling over. He fought on until he could no longer endure the pain, and called for help. The hotel staff rushed him off to a nearby hospital.

As it became clear, the whole time dad was in Japan, he had been working through acute appendicitis. As the doctors prepared him for surgery they told him that, had he gone to Narita as planned, he wouldn’t have survived the flight home. Thanks to their prompt diagnosis and appendectomy, dad made a full recovery (albeit with a slightly-longer-than-planned stay in Ikebukuro).

Though I’m sure that the story has been lovingly embellished over the years, my dad’s experiences in Japan would leave a very strong impression on me.

On hearing that his illness had kept him from returning to his young family, many of dad's new business connections gifted him with toys and trinkets to bring home for us. Because of that kindness, I spent my days as an infant playing with Japanese toys, and at night a mobile that played MIDI-renditions of Japanese folk songs lulled me to sleep. As my early years rolled by, dad would return again to Japan on business and each time he would bring new stories and curiosities home for us. As I grew old enough to understand, he told me in more detail about his trips and in doing so, planted the seed for my interest in the country, its people and particularly its language.

By the time I was a teenager, dad was travelling a lot more for work. He'd visited the USA and Canada; Germany, Spain and all across Europe. He often went to Hong Kong and Shanghai; one summer he spent a few weeks in the arctic circle in Sweden. Every time he would come home, I'd eagerly interrogate him about the places he'd been and the things he'd seen. Though he was likely exhausted from the journey, he never seemed to mind and his stories filled me with an insatiable urge to travel, to see the world and immerse myself in other cultures.

When the time finally came for me to choose my university course I saw an opportunity. Leaning into both my desire to travel and my early connection to Japan, I decided to study Japanese language and social anthropology. Not only would I be able to fully dive into learning another language, the course would also include a year living abroad in Japan. Dad thought it was a fantastic idea. He believed that studying a subject that I had chosen entirely for myself would be a great motivator.

In August of 2005 I moved to Tokyo to attend Aoyama Gakuin University.

Immersion was everything I'd hoped it would be. Living and studying in a new culture meant that every single day was filled in equal part with excitement, challenge and new things to learn. Dad was right - learning a language in context was giving me a drive and passion that I hadn't felt before. I called home often and dad always seemed as eager to hear about my experiences as I had been to hear his.

As my time in Tokyo wound on and I passed the mid-point of my year-abroad, my inevitable return to the UK began playing on my mind. I didn't want to leave, but at the same time I had started to get quite homesick. Sensing this, dad called me whilst he was on a business trip to China. He told me that, at the last-minute, he was able to swing a flight home with a three-day Tokyo transfer. He was going to be able to come and see me and I couldn't have been happier. Before his plane departed Guangzhou, he called me again for one one last bit of silliness. He told me to be careful - I’d been away from home so long that he might not recognise me anymore. I decided to call his bluff and I went to greet him at Narita with an airport-pickup-sign saying, “Dad”.

Funnily enough, I didn’t need the sign.

Within our family, our experiences of visiting Japan are something very special that only my dad and I share. Those three days together in Tokyo, his stories became our stories and I felt closer to him than I ever had.

I took great joy in showing him around my university campus in Aoyama. In return, dad took me to Ikebukuro and we talked about how the city had changed since the 80s. We visited the Sunshine City Prince Hotel where, tears welling in his eyes, we retraced the story together. Most fondly of all, I remember taking dad for dinner at my local yakiniku restaurant. I will never forget the look of pride on his face when, for the first time, he heard me chat confidently with the staff in Japanese.

With a wry smile he said, “I guess you really do speak it. And to think this whole time I thought you were just faking it to get a holiday”.

Ultimately, my time at university in Japan ended abruptly with a breakup. I’ll spare the specifics but, with the semester about to end, I decided that the best thing to do was come home early. As always, dad was nothing but supportive. Whilst I struggled to hold myself together, he quietly reorganised my flights, and arranged to have my belongings shipped home. He called or emailed often; silly, light-hearted things to check in and to distract me from my now ex-girlfriend. Most of all, he said, he wanted me to remember what had motivated me to be there to begin with. He wanted me to leave Japan feeling happy again.

On a grey summer’s day in 2006, I landed at London Heathrow. As soon as the wheels touched down on the rain-soaked tarmac, I met with the overwhelming feeling that I’d made a terrible mistake in leaving Japan early. For all the promise of me living abroad, it felt as if I had bottled it at the last minute. The plane was held at the gate and I wallowed until we were allowed to disembark.

Forty minutes late and fighting back the tears, I collected my luggage. I couldn't shake what dad had said to me. I hadn't left feeling positive about my time in Japan; I was feeling profoundly ashamed. I shuffled out into the arrivals lounge to see dad waiting for me. I felt like I had let him down, but he didn't look disappointed. Instead, he wore a wide grin on his face. I looked down and in his hands he held a huge home-made sign that read, simply, “Son”.

He didn’t need the sign.

Many years later dad would be struck with stump-appendicitis, a rare secondary condition that only occurs in people who have had an appendectomy. Though the condition itself was treatable, the late diagnosis and his local hospital's poor handling of the new surgery would cause increasing complications in the years that followed.

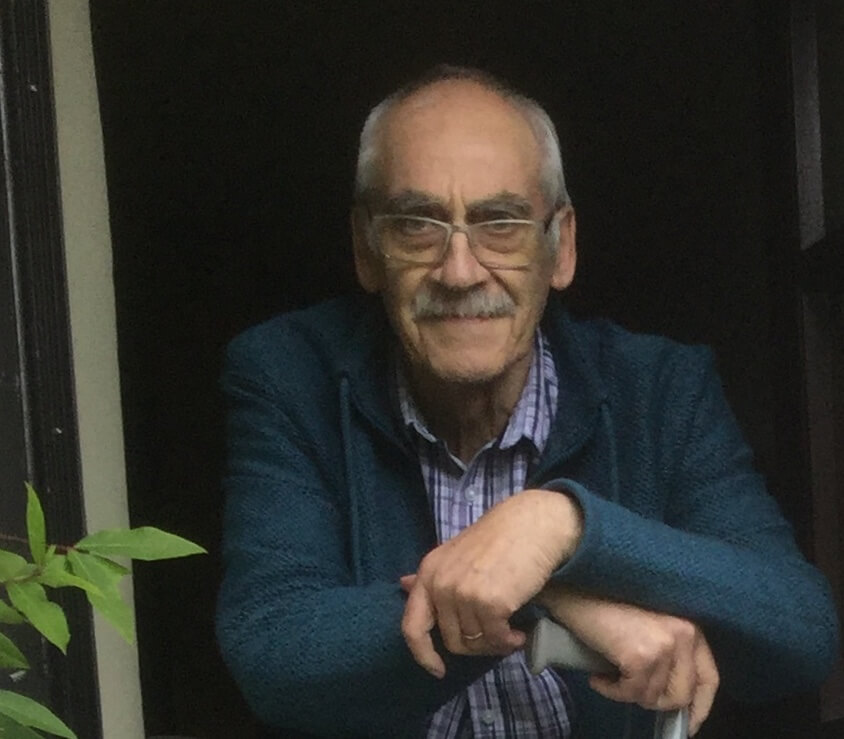

After more than a decade of strength, dad passed away in hospital on the morning of September 13th 2021. Covid restrictions meant that my brother and I had to say our final goodbyes as he slept peacefully. My mum remained with him until the end, holding his hand.

Despite the almost constant pain caused by his condition, my dad was never anything less than himself and that is how he will live on in my memories; the same funny, supportive and selfless giant of a man that he had always been. More than anything, he was a constant inspiration who helped me to go out into the world with confidence and an open mind. For that, I am so very lucky to have called him my father and I will miss him dearly.